The story of the Underwater Astronaut Trainer located at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, began in 1986, the same year the Challenger accident happened. At the time, I was a NASA Marshall Space Flight Center astronaut training manager assigned to train the first Japanese astronauts for the Spacelab-J (SL-J) mission. With that mission put off indefinitely by the grounding of the shuttles, I was ordered home from Japan and given a number of short-term assignments until SL-J got a launch date. When I read in the Huntsville Times that the USSRC was going to build a swimming pool to teach Space Camp and Space Academy students the principles of operating in weightless conditions, I was intrigued. Since I was a scuba instructor and a diver in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator at Marshall Space Flight Center, I thought a similar tank could be built at the USSRC.

The director of the USSRC at the time was Ed Buckbee. I didn’t know Ed and he didn’t know me but I soon discovered we had something important in common. We were both from West Virginia. That was a good introduction, I figured, and I was right. Ed invited me over to his office at the museum for a talk about my idea. I worked up a proposal, and asked my girlfriend, a graphics designer, to help me put together a pitch. A few days later, I delivered my proposals and convinced Ed that a water tank could be built to train his students and also might be used by professional aerospace companies. To move things along toward approval, I told him I would also build a realistic underwater space suit for the students to wear during simulations.

Ed was a bit dubious. For one thing, the concrete pad was already poured for a swimming pool so anything different would have to go on that footprint. Also, the height of the roof where the pool was to go was already set so there was a limitation there. He also said his budget was small and told me how small. “Can you do it for that amount?”

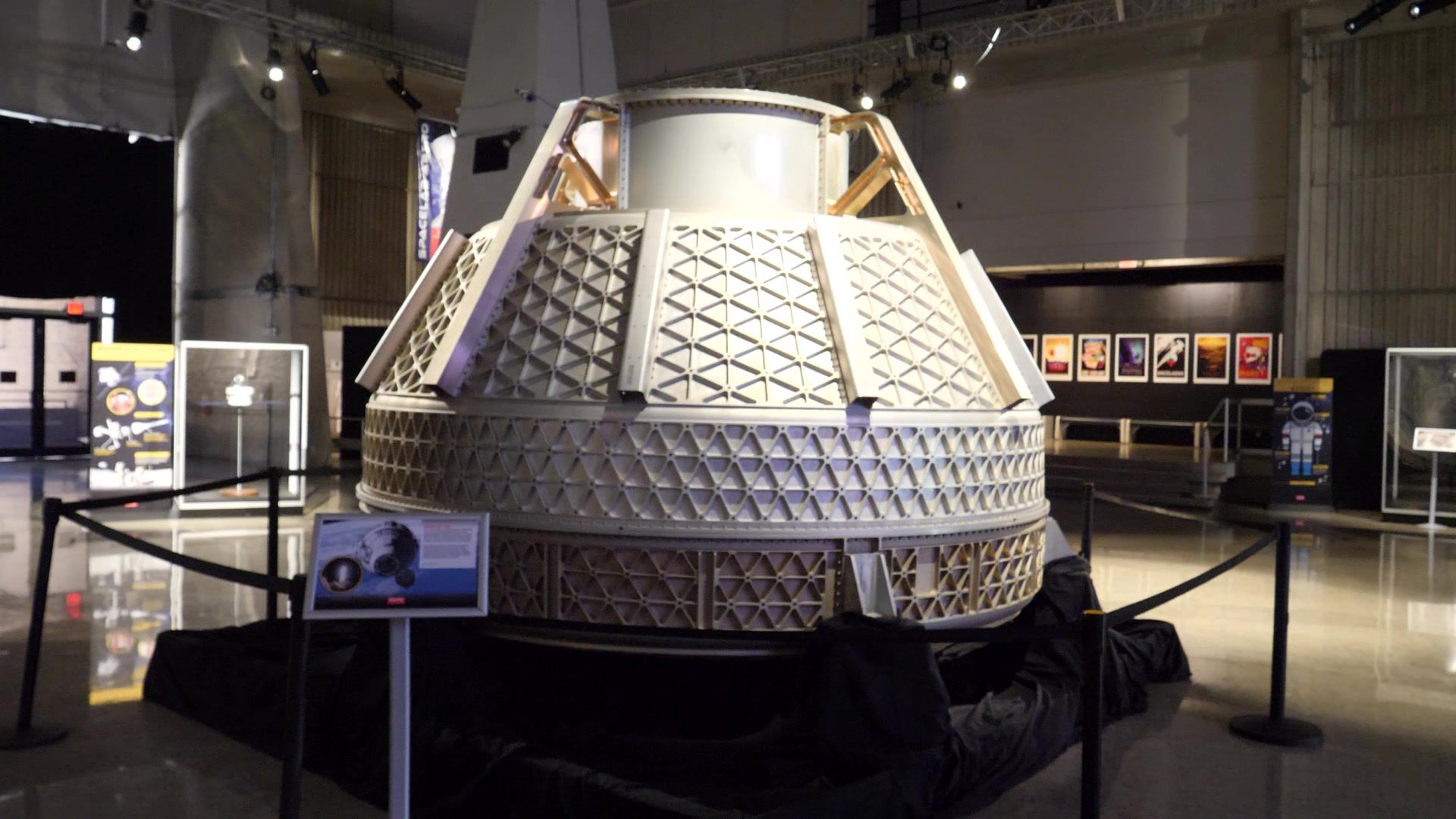

“You bet I can!” I promised, even though I had no idea if I could or not. To fit the foundational footprint and height limitations, I sketched out a 30-foot diameter, 24-foot deep steel cylinder with portholes at various levels. Essentially, it was a mini-NBS. When an architectural firm put my sketch out to potential contractors, it was Chicago Bridge and Iron, the same company that built the NBS, that delivered the low bid. It was low enough that I had money left to purchase scuba gear. Ed asked me to come up with a name for the new tank and I suggested that it be called the Underwater Space Simulator (USS). He gave that some thought and said, “We’ll call it the Underwater Astronaut Trainer,” and so it is the UAT to this day.

Chicago Bridge and Iron soon arrived with their equipment and crews and, in about two weeks, built the UAT using the same techniques and some of the same people who’d built the NBS. Often coming over to observe the progress, I loved the smell of the arc welders as each level went up because it meant progress.

Soon, however, I realized we had forgotten something. With head bowed, I went to Ed and confessed we needed a platform around the top of the tank to train the students. After scowling for a while, he gave me $3000 and said that’s all he had. I found a small local vendor who was willing to do the work for that amount. Together, we designed the platform plus steps into the water, all made from stainless steel.

In parallel to the design and construction of the UAT and its platforms, I purchased scuba equipment at a big discount from several manufacturers that liked being associated with Space Camp. To fill the scuba tanks, I also got a discount on a rebuilt air compressor from the McWhorter company in Birmingham. As promised, I designed a space suit simulator which included an underwater space-like helmet manufactured by the Lama company in France. We purchased two of them. I later used one of them to train David Letterman, the television late night host, for a proposed underwater show. Although the show never happened, that training was shown by Letterman when I was on the air with him to publicize my book Rocket Boys and the movie October Sky.

After the tank was filled with water and tested for leaks, the facility was ready but now we needed to figure out how to train the students and the supporting UAT staff. Assigned as the UAT’s first manager was a young woman named Lori Cash Kegley, a recent graduate of East Tennessee State University. She wasn’t scuba certified but was eager to learn and I was happy to have her as my counterpart at the center.

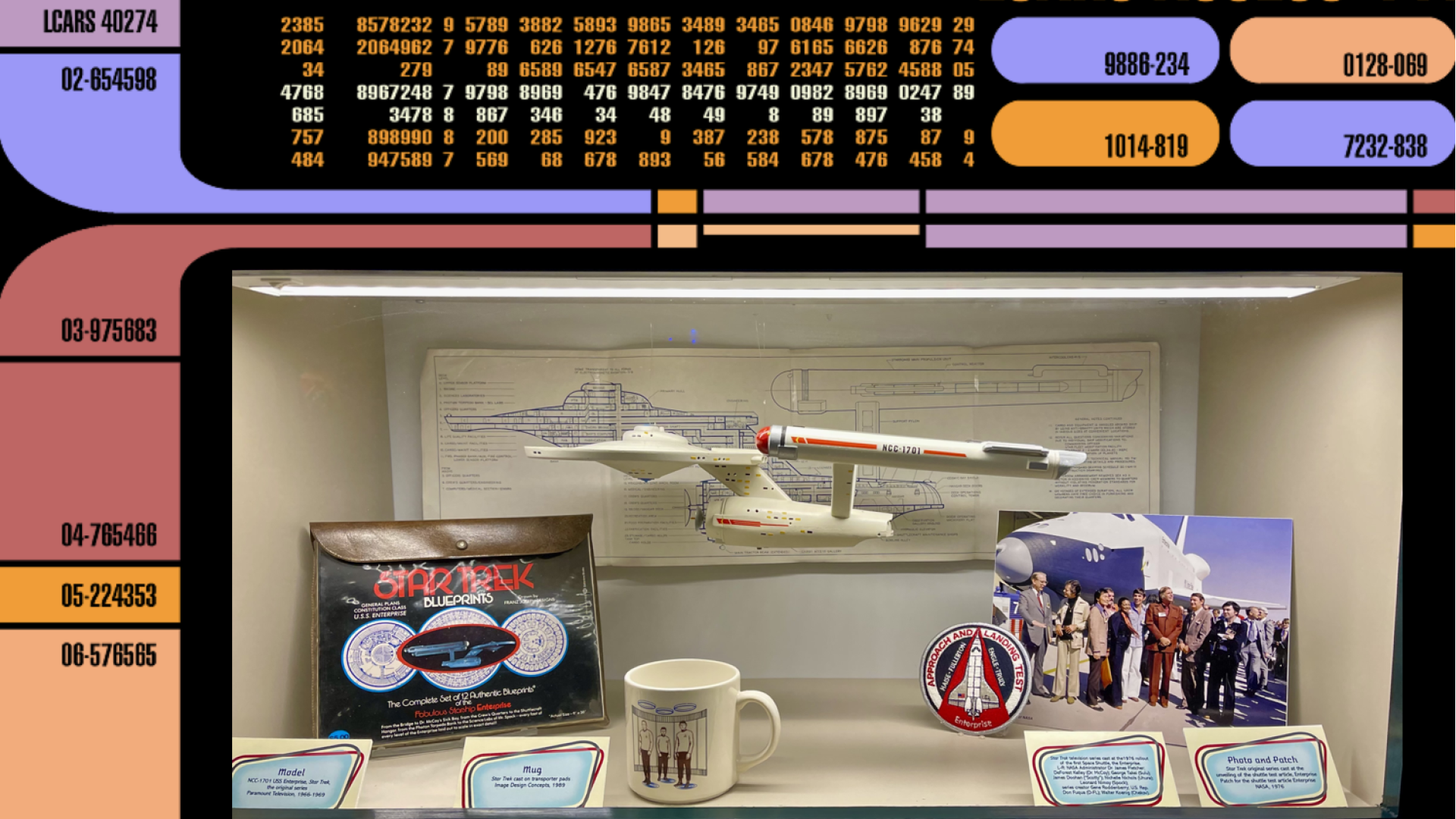

Up until that point, all my labor was donated but when Ed asked me to also train the students, I knew I would need permission from Marshall Space Flight Center to work part-time at the UAT. After that permission was granted, I formed a company called Deep Space and staffed it with local divemasters and scuba instructors I trusted. After working up a training methodology that would take students to the bottom of the UAT on scuba within a half hour after they entered the water, we asked for some young volunteers to make sure it was safe and viable. While we were testing our instruction techniques, we also installed some scrounged mockups from the NBS in the UAT, mostly discarded Hubble Space Telescope or Skylab training hardware, and created additional lesson plans to teach the science and human factors requirements of micro-gravity in space. Once everything was in place, we trained our first students, those on the engineer track of Space Academy.

Deep Space would train students in the UAT for nearly three years until NASA ordered me to go back to Japan to prepare the astronauts for Spacelab-J. During that time, we trained hundreds of Space Academy students and also trained astronauts including Payload Specialists Ron Parise, Sam Durrance, and Byron Lichtenberg. Astronaut Owen Garriott sometimes joined us and gave advice. After Deep Space was disbanded, UAT manager Lori Kegley, now fully scuba-certified, hired in-house instructors to follow the lesson plans we had pioneered.

The UAT is still in use to this day. All of us involved during the design, construction, and initial training of students there are proud to have been part of the history of this astonishing facility which is now expanding to add more public programs. With the addition of new underwater helmets that require no scuba training, we expect to see many more people underwater in the UAT having fun while learning something of what it’s like to live and work in space.